Introduction

Nuclear energy: between emotional debates and incomprehension, it is time to really understand what nuclear energy is, in what forms we exploit it, and future projects to face present and future environmental challenges.

We will first explore the basic principles of this energy by looking at how an atom and its nucleus are made up.

Next, we will explore our engineering techniques to harness this energy.

And finally, we will understand what nuclear fusion consists of, its advantages and disadvantages, and the various future projects for exploiting this energy.

Nuclear energy: What is it?

The definition of nuclear energy depends on the context of use. We are going to look at what nuclear energy is at the particle level.

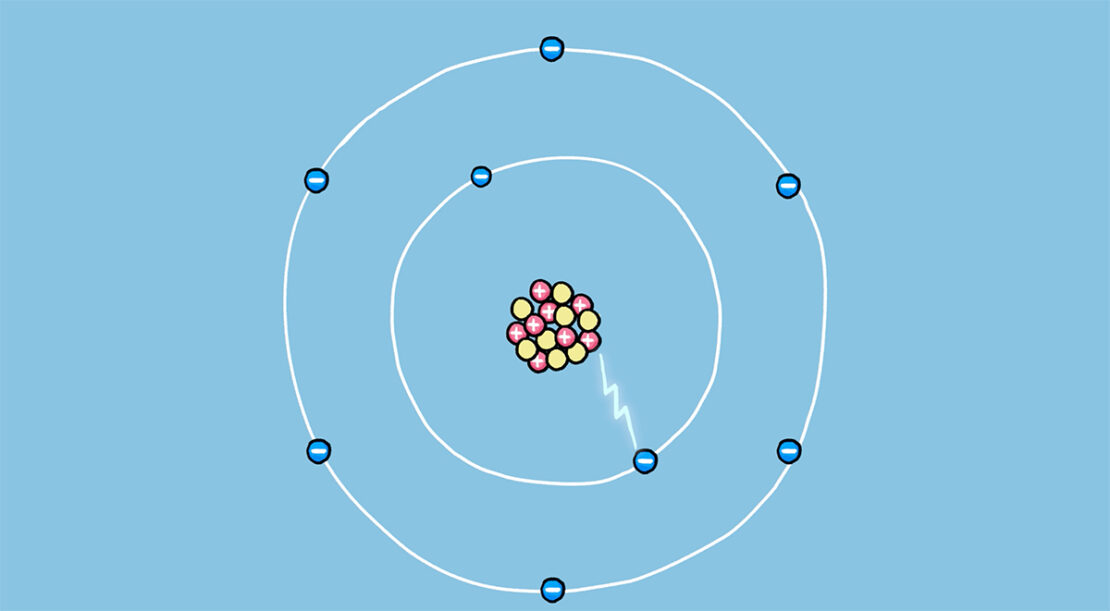

An atom is made up of a nucleus and electrons orbiting around it. The nucleus is made up of protons and neutrons. These particles are called nucleons. In order for these nucleons to hold together to form the nucleus, cohesion is present between them.

Nuclear energy is the energy associated with this cohesion. We can imagine this cohesion as a set of strings that bind the particles together. The tighter these ropes are, the stronger the sustaining energy. Releasing nuclear energy amounts to releasing the cohesive energy of the particles that make up the nucleus of the atom (nucleons). Release those taut strings that hold the nucleons together and see the energy coming out!

But how do you release those strings?

There are two ways for an atom to release nuclear energy: by nuclear reaction or by radioactivity.

Radioactivity

We designate certain atomic nuclei as “unstable” when the difference between the number of neutrons and protons in the nucleus is too great. To regain this stability, the nucleus decays into another nucleus. This disintegration emits particles and energy. Radioactivity refers to this disintegration. An atom is said to be radioactive when it spontaneously disintegrates emitting a significant amount of energy.

There are three different types of radioactivity: alpha beta and gamma, but we’ll explore them in another article.

When a radioactive atom decays into another, by losing a neutron for example, this atom will become, in a way, another version of this same atom. This new version is called an isotope. Two atoms are isotopes if they share the same number of protons but their number of neutrons differ.

For example, the hydrogen atom has only one proton. There are two isotopes of hydrogen: deuterium and tritium. Deuterium has one neutron and one proton. Tritium has 2 neutrons and 1 proton, which makes it a radioactive atom. If the tritium releases a neutron, it will become a deuterium atom and will have given off a large amount of energy.

Nuclear Reaction

Unlike radioactivity, a nuclear reaction occurs with the interaction between an atomic nucleus and any other particle. A nuclear reaction results in a more stable nuclear configuration. Each nuclear reaction releases a certain amount of energy.

There are two types of nuclear reaction: fission and fusion.

Fission

Nuclear fission takes place when a neutron strikes the nucleus of an atom and this nucleus splits into two lighter nuclei. During this fracture, a large amount of energy and several neutrons are released. It is this energy that we use in our nuclear reactors.

Within a reactor, a neutron is sent at high speed on a uranium 235 atom. This atom - being unstable - fragments releasing a large amount of energy accompanied by neutrons. These neutrons will then collide with new uranium 235 atoms which will in turn split. A chain reaction is set in motion.

This chain reaction produces a lot of energy in the form of heat, which will heat liquid water into steam, powering a turbine to produce electricity. Simple isn’t it?

For fusion, we also want to exploit the heat of reaction, but this heat is not as easy to obtain.

Merge

Fusion is combining two light atoms into one heavy nucleus. But how can energy be produced during this reaction?

You have probably already heard of the formula:

$$e = mc²$$

$$e: energy \ m: mass \ c: speed \ of\ light$$

Let’s use this formula to understand the basic principle of fusion.

We know that the mass of an atomic nucleus is less than the sum of the masses of the nucleons that compose it. How is it possible? If we build a wall with 3 bricks, the mass of the wall will be equal to the sum of the masses of the bricks, in this case 3 bricks.

This is not the case at the atomic scale. This difference between the mass of the nucleus and the mass of the nucleons that compose it is called mass defect.

It is this mass defect that we are going to exploit by combining two light cores into one heavy core. The latter actually represents the binding energy that will be released as kinetic energy. During the fusion of atoms, the collisions between particles degrade the kinetic energy into thermal energy, and it is this abundant heat that we want to exploit within a reactor.

The amount of energy to fuse two atoms is very large. For two nuclei to combine, they must overcome the electrical repulsion between them, due to their respective positive charge. Overcoming this barrier requires a tremendous amount of energy under classical mechanics. Fortunately, quantum mechanics (the infinitely small), has shown us that this barrier can be crossed by the tunnel effect. This effect, only observable by quantum mechanics, stipulates that a particle can cross a sufficiently fine obstacle, with an energy smaller than the minimum energy to cross the obstacle.

This logic is completely counter-intuitive and shows quantum complexities that we are not going to discuss here for obvious reasons…

Let’s just note that thanks to this barrier effect, the amount of energy to fuse two atoms is smaller than expected. But it is still very important.

We therefore need, to fuse two atoms, an environment under high pressure and temperature. Which atom requires less temperature and pressure to fuse together? The energy yield of the reaction must be positive: in other words, less energy is used than it is produced.

As seen before, atoms with a significant mass defect will release a large amount of energy if this binding energy is released.

But we must also be able to fuse these atoms. For this, we use atoms with light nuclei with a significant mass defect, such as hydrogen.

On our Sun, fusion reactions consist of the fusion of 4 protium nuclei into a helium 4 nucleus. This is the most exothermic fusion reaction, but it requires pressure and temperature conditions that we only find on the surface of the Sun and that we would have too much trouble replicating on Earth.

A more feasible reaction of fusing two deuterium atoms into a helium atom and a released neutron, noted below. The advantage of this reaction is the absence of radioactivity in the final product.

$$^2 _1D+ ^2 _1D⟶ ^3 _2He(0,82 MeV)+ ^1_0n(2,45 MeV)$$

Moreover, deuterium is very abundant in our seas. Indeed, one cubic meter of seawater contains 33 grams of deuterium, which can be extracted by electrolysis.

But this reaction does not release much energy compared to the fusion of an atom of deuterium and tritium, as we can see noted below:

$$ ^2_1D + ^3_1T \longrightarrow ^4_2He (3,52MeV) + ^1 _0n (14,1MeV) $$

We know that we have deuterium in (almost) unlimited quantities. But what about tritium? The real problem lies in obtaining the tritium.

Tritium is not present in nature and the only way to get enough of it is to bombard a neutron on an atom of Lithium 6, an isotope of Lithium which is very rarely present in nature.

The idea is therefore to use the neutron created in the fusion of a deuterium and a tritium, and to put it in contact with a lithium 6 atom to produce tritium.

There are two problems that arise:

- We therefore use fusion to produce tritium. But what if we don’t have tritium at the base to trigger the fusion reaction?

- The technology used to produce this tritium called “breeding blanket” is still very expensive and therefore less than 1% of the interior surfaces of a fusion device are covered with it.

- Lithium 6 is very scarce in nature. It represents 7.8% of the global stock of lithium in the world.

Le problème de l’approvisionnement du tritium et du lithium 6 est un des plus gros défis de la fusion nucléaire. Beaucoup de recherches restent encore très actives sur ces sujets comme des propositions de séparation de lithium intégrée aux systèmes afin de pouvoir utiliser le lithium 7, encore très abondant dans la nature.

La fusion nucléaire présente encore de multiples défis avant de pouvoir être industrialisée. Mais ces défis sont résolubles et la recherche dans le domaine reste très active. La fusion nucléaire est une des sources énergétiques les plus plausibles pour remplacer le pétrole dans le prochain centenaire, en terme de quantité, mais aussi de propreté. Les emissions de gaz à effet de serre reste très basse par rapport à la quantité d’énergie produite.Mais il faudra encore attendre que la recherche scientifique résolve ses différents problèmes.

The problem of the supply of tritium and lithium 6 is one of the biggest challenges of nuclear fusion. Much research is still very active on these subjects, such as proposals for the separation of lithium integrated into systems in order to be able to use lithium 7, which is still very abundant in nature.

Nuclear fusion still presents multiple challenges before it can be industrialized. But these challenges are solvable and research in the field remains very active. Nuclear fusion is one of the most plausible energy sources to replace oil in the next century, in terms of quantity, but also cleanliness. Greenhouse gas emissions remain very low compared to the amount of energy produced. But we will still have to wait for scientific research to solve its various problems.

Resources

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_energy

[https://nuclearsafety.gc.ca/eng/resources/radiation/introduction-to-radiation/atoms-nuclides-radioisotopes.cfm#:~:text=Atoms are stable when,%2C the atom becomes unstable] (https://nuclearsafety.gc.ca/eng/resources/radiation/introduction-to-radiation/atoms-nuclides-radioisotopes.cfm#:~:text=The%20atoms%20are%20stable%20when,%2C%20l atom%20becomes%20unstable).

[https://www.futura-sciences.com/sciences/dossiers/physique-voyage-coeur-matiere-176/page/7/](https://www.futura-sciences.com/sciences/dossiers/physique -travel-heart-matter-176/page/7/)

[https://www.andra.fr/les-dechets-radioactif/la-radioactivite/explication-du-phenomene](https://www.andra.fr/les-dechets-radioactif/la-radioactivite/explication- of-the-phenomenon)

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effet_tunnel

[https://www.iter.org/fr/sci/fusionfuels#:~:text=To obtain deuterium%2C il,for scientific and industrial purposes](https://www.iter.org/fr/sci /fusionfuels#:~:text=To%20get%20of%20deut%C3%A9rium%2C%20il,%20for%20scientific%20and%20industrial purposes).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092037961930835X?via%3Dihub